Dr. Terence Love, Curtin University, Perth Western Australia

© T. Love 2006

Critical review of professional design practice, creativity and quality improvement in design is weak in the design literature relating to design processes and the computer technologies that support them. This paper takes a systems perspective focusing on the role of professional design practice and its relationships with creativity, quality improvement and computer hardware and software used by designers.

The analyses developed in this paper indicate that professional design practices along with tools, processes and regarded as ‘creative’ or supporting creativity structurally inhibit creativity and quality improvement in design. In essence, that:

The paper demonstrates the value of a systems approach in identifying counter- intuitive outcomes.

Keywords: design research, professional practice, systems, creativity, quality improvement

The concept of ‘professional design practice’ is widely regarded as a central element of:

This paper takes a systems perspective focusing on the role of professional design practice. The paper looks at the adverse implications and effects of the current uncritically held assumptions that use professional design practice as a basis for understanding and conceptualising design. This paper problematises professional design practice and the relationships between professional design practice, creativity, quality improvement and computer hardware and software used by designers through the lens and tools of systems analysis. It applies a systems perspective to:

Critical review of creativity and quality improvement in design is weak in the literature relating to design processes and the computer technologies that support them. The concepts of ‘creativity’ and quality improvement are regarded as a central to competent design practice. One aspect of this lack of critical attention is the uninspected assumption that processes and technologies that support professional creative practices must in themselves support creativity and improvements in quality.

The bodies of literature on creativity and quality improvement practices, methods and strategies have mainly depended on assumptions about stability and slow change in professional design practices. This is particularly evident in engineering design and architecture fields. Across the literatures of design, professional design practice, design creativity and quality improvement in design, the reader is presented with a self-assured discourse as if the issues and relationships between the key concepts (design, professional design practice, creativity, and quality improvement of design) are unproblematic, and the relationships between them can be assumed on face value. These apparently unproblematic assumptions relating professional practice, creativity and quality improvement have propagated into both the culture of design practice and the public understanding of design. Together they have lead to many deeply held misunderstandings. One consequence is these unquestioned professional and public assumptions have led to the presumptions that computer tools and processes used in the professional practice of designers - e.g. the Mac computer and graphic software – intrinsically support creativity and quality improvement of designed outcomes. Critical review, however, suggests the opposite; that computer systems that directly support professional design practice act to inhibit creative outcomes and have an adverse effect on quality improvement in creating novel, innovative designs.

The next sections use systems approaches as the basis to problematise the idea of professional design practice and the relationships between professional design practice, creativity, quality improvement, design management, design education, and computer systems for ‘creative’ professionals. The system perspectives applied in this paper indicate that the current tacit use of the concept of professional design practice is unhelpful in several ways. The analyses indicate that professional design practice:

These outcomes are counter-intuitive and challenge received wisdom. This identification of radical errors of commonly held understanding is a common outcome of the application of systems tools to complex situations whose understanding has been dominated by uninspected assumptions and the application of human intuition (Forrester, 1975). Typically, the use of systemic analyses demonstrates the intrinsic and generic weakness of human intuition in addressing complex situations and situations involving subjective understanding or self-reflection.

The systems viewpoint used in this paper that underpins the critique of professional design practice derives from three elements:

The perspective on design activity is holistic across time in such a way that it brings into visibility the effects of formal and informal education and professional formation of designers, the stabilising effects of professional design practices and the ways these, together with hardware and software, bound and shape opportunities for design into routinised types of solution. This viewpoint also exposes the ways that professional design practice forces a path dependency that dominates design output; restricting it primarily to incremental changes. This is regardless of the fact that many incremental changes may superficially appear different from each other whilst they are in essence morphological variants of routine solutions created within the bounds dictated by professional design practices.

These system analyses assume that all designs that have been lumped under the heading of ‘creative’ are not necessarily so. The perspective assumes that routines of design activity create path dependencies in which ‘creative’ designs are produced that are bounded by these routines. This is in the same way that using a hammer as one’s only tool bounds what can be created, even when the hammer is used in unusual ways. This differentiates between routine design activity leading to routine design solutions, and alternative approaches that have the potential to create solutions that lie outside what is possible within the bounds of professional design practice. In that sense, it defines novel, innovative and creative solutions as distinct from designs created within professional design practices. It allows and assumes that professional practices are likely to be different in different design sub-fields.

Taking a broader systems perspective indicates that many tools, processes and practices regarded as supporting creativity, in fact structurally inhibit creativity and in many cases structurally inhibit quality improvement in design activity. This paper applies systems perspectives and critical analysis to reveal problematic thinking associated in systems terms with local sub-optimisation. That is, thinking that is not coherent across the whole systems but which reifies ‘local’ conditions and then presumes they make best sense at a larger scale.

Taking a systems perspective, the conceptualisation and definition of professional design practice is marked by three problematic characteristics:

These factors indicate that the concept of professional design practice is likely to be problematic in theoretical, hegemonic and practical terms.

In exploring professional design practice, it is immediately evident that there are significant differences across the hundreds of design sub-fields. The division of the overall field of design into three streams, ‘technical' design, 'art-based' design, and ‘other’ design, is useful. Technical subfields of design are those that require some knowledge of mathematics and science, e.g. engineering design software design, building construction. ‘Art-based design sub-fields are typically derived from craft-based sub-fields of design previously taught in vocational colleges outside the university system. They are typified by the 40 or so design sub-fields taught in’ Art and Design’ courses in the UK. The ‘other’ subfields of design are those that are neither ‘technical’ nor ‘art-based’.

The idea of professional design practice is a cornerstone of both ‘technical’ and ‘art-based’ design subfields. Preliminary findings from unpublished research by the author indicate that together the technical and ‘art and design’ groupings comprise just over 50% of the overall design field with the technical design group being around 10 times the size of the Art and Design group. A superficial review of the literature of ‘other’ design fields indicates that the idea of professional design practice is less central to the ‘Other’ design sub-field group. This may be because these ‘other’ design sub-fields are more recently established and have not yet had time to professionalise, or because they are already professionalised with a different focus. For example, a high level of competence in design is a primary skill of lawyers. They design courtroom arguments, strategies, compensation arrangements, etc. In spite of the primary role that design plays in lawyers professional lives, they are regarded as law professionals rather than (say) ‘legal argument designers’.

This paper problematises professional design practice in the technical and art-based design sub-fields only. Design education in technical and art-based sub-fields of design is intended to educate to a specific level of competency in a range of behaviours, knowledge and skills defined by an ideal of professional design practice in the relevant subfields. For each sub-field, there is a clear idea of what these professional design practices are, for example, in terms of being a graphic designer, a mechanical engineering designer, or a computer software designer. In many design professions, these idealised pictures of professional design practice are clearly specified in terms of knowledge, competences, or general attributes by professional institutions such as the Design institute of Australia, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, ASME, and the British Computer Society.

In general, the concept of professional design practice refers to a description of a set of behaviours, knowledge and skills regarded by peers in specific design sub-fields such as graphic design, information systems design, engineering design, interior design, architecture etc as necessary to be competent to address a set of specified tasks. In each of the sub-fields of design that takes a professional position on design practice, professional design practice is defined in terms of competencies. These include, for example: the ability to manage colour in particular ways, to understand particular aspects of type, to understand the semiotics of objects, to understand physical behaviours, to understand and know particular examples of good practice in special, to understand culture, to know and have heuristics for designing communication artefact such as websites, etc. A dimension of competence in professional design practice is the ability to use particular tools. In earlier times, it was skills with e.g. Letraset and slide rules. Currently, design practice competencies are dominated by skills with particular computer hardware and software such as Quark Express, Catia, and InDesign. Thus, these professional competencies are connected to current state of art and recent past history of design practices and relate to what is understood by members of a design sub-field as state of art competence. In many design fields, these behaviours, knowledge and skills associated with competence as a professional designer are typically acquired via formal education processes such as university study combined with experience in working as a designer.

The idea of professional design practice also affects design research in ways that are rarely critically inspected. For example, in many design research projects, underlying any research into design activity is a judgement of whether the design activity was undertaking in a professional design environment. In other words, researchers differentiate between design as done by designers and design done by anyone else. The idea of professional design practice also underpins studies contrasting the behaviours, knowledge and skills of ‘expert’ designers with ‘novice’ designers. In essence, these studies are attempting to define the characteristics of competent design practice

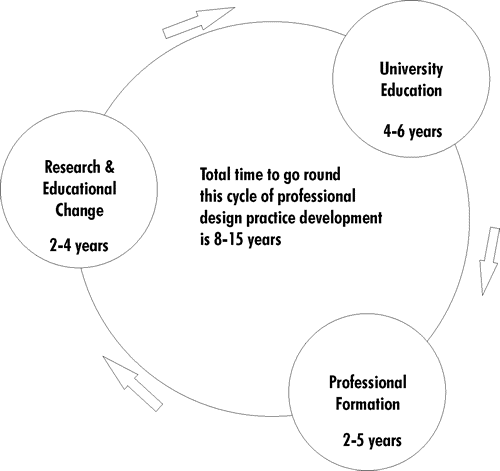

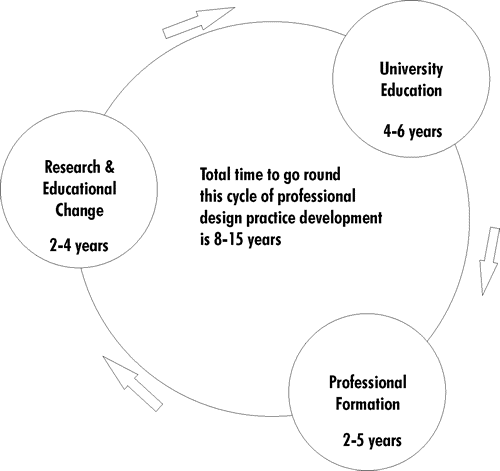

Professional design practice adopts changes slowly. It takes in the order of a decade for an innovation in design practice to be propagated into the next generation of design professionals. For design professionals who gain their education through a combination of university and professional formation, change in professional practice occurs via a feedback loop comprising:

Fig 1: Cycle of Professional Design Practice Development

It requires a designer to achieve status of “design professional” to be a valid target of university researchers investigating the state of art of competent design practice to identify what is appropriate to teach. This means that effectively the point of interest is the lower left hand sector of Fig 1 above. It then takes a change a whole cycle to propagate back to professional designers.

Changes will of course be continuous. The implication is, however, that each single change will have around 10 years lag before it becomes more widely adopted through these mechanisms. This corresponds well with the typical rates of change in innovation for significant products (Ives, A. (2006), Stephenson Lecture, Perth: IMechE).

Mapping the change mechanism in this way points to a need for short cuts. One possibility is to situate education specifically relating to professional design practices as late as possible in design education. Doing this presumes, however, that other parts of the course are not specific to professional design practice and begs the question of how much design education is a professional skill.

The concept of professional design practices is embedded deeply in the culture of all the major constituencies of technical and art-based design sub-fields and has become closely linked to the ideas of creativity and quality improvement. For example, creativity as a skill for graphic designers is now so embedded in the idea of professional practice and status that the creative output of someone who has not followed the professional design practice pathway is regarded as an amateur, less skilled, and of less status and value.

Professional design practice by its nature acts against creativity. This is because professional design practice is in essence the definition of processes of routinisation. This focus on improving routinisation acts against non-routine approaches to designing and the design of non-routine solutions.

A dominant effect limiting creativity is the glacial speed of change in professional design practices with its decade long feedback loops. This contrasts with the rapid pace of change of novel, innovative solutions in the present world.

It is important to differentiate between creation of novel innovative design solutions and designs based on small incremental advances perhaps using arbitrage to combine well-established ideas from different fields, e.g., mechatronics design. Where incremental changes are small, require little new knowledge, and where change is slow then design activity bounded by professional design practice is well suited , regardless of the very slow processes of change of design practice standards,.

Skills and competencies that go beyond professional design practices that are better suited to creating novel, innovative, ‘creative’ outcomes are likely to spread slowly where educational and organisational learning models in design sub-fields are constrained and slowed by the structural effects of slowly changing structures of professional design practice.

Anecdotally, from my own experience as a designer, creating occasional novel designs and learning about radical creative outcomes instituted by others has only been possible by ignoring the constraints of institutionalised professional design practices. I suspect this is true for most designers that are interested in rapid and novel change.

Quality improvement processes and models are now well developed in a wide variety of design sub-fields. Quality improvement processes align well with the idea of tightly bounded professional design practice definitions, routinisation, and the avoidance of radical change in processes and outcomes. They are especially well developed in the hundreds of technical design disciplines in which prototyping and modelling is grounded on the use of mathematics and modelling techniques form the physical sciences. Quality improvement of designing of routine design outcomes is well supported by a cluster of stabilising factors. These include: definition of competencies for professional design practices (different in different sub-fields); education processes tied to professional design practices; explicitly defined design processes (e.g. VDI 2221 (VDI-Verlag, 1987)); well established standards (material properties, pressure vessel design, testing processes); routinisation of business processes; and the adoption of standardised, and well tried, approaches to quality improvement.

Quality improvement undertaken within the context of professional design practice focuses on improving routine techniques and practices. Structurally, professional design practices are likely to compromise processes of quality improvement aimed at creative, novel, innovative designs that go beyond the routine design and design processes as bounded by professional design practices.

Quality improvement processes appropriate to non-routine creative, novel, innovative design situations require radical differences from quality improvement methods designed for routine design activity undertaken within the bounds of professional design practices. Quality improvement processes targeting improvements to routine design activity potentially compromises non-routine design and can inhibit innovation when applied to situations marked by creativity, high levels of radical change, and novel, innovative and unusual designed outcomes.

All approaches to quality improvement target either:

The first, reducing the rate of defect formation, offers significant benefits over the second in most areas of human endeavour. In design activity, this is especially true because the resources needed to avoid faults in design are financially and time wise orders of magnitude less than repairing designed artefacts after they have been produced.

In novel design situations involving high levels of creativity and innovation that go beyond existing professional design practice, it is likely that the only persons with skills to be able to identify and correct the root causes of defects are those whose skills go beyond the norms of professional design practice in those areas. Those operating within the skills and bounds of professional design practices are likely to identify the wrong roots of failures (see, for example, analyses by Forrester (1975)). Similarly, designers whose primary focus is routine design are likely to be prone to either misinterpret or incorrectly identify the actual faults in the created designs, or, if they identify faults, are likely to be mistaken in their suggestions for repairing those faults.

Developing quality improvement approaches appropriate to novel, innovative, creative design requires reverting to first principles in terms of identifying root causes of defect production as early as possible. In truly novel and innovative design situations, this requires the development of ad-hoc quality development processes. A primary issue in undertaking these is to obtain a clear understanding of potentially counter intuitive issues as revealed for example by ‘whole of system’ analyses. It is identifying and addressing these counter intuitive issues that are the primary aspects of quality improvement approaches aiming at reducing defect formation in the design of novel, innovative, creative designs that lie outside the remit of the routine outcomes available through professional design practice and conventional quality management techniques.

The concept of professional design practice strongly underpins the management of design activity in many organisations. In design-sub-fields that are regarded as professions, design management often depends heavily on the idea of a singular model of professional design practice. The idea of a single standard of professional competence in design practice is especially strong in technical design subfields such as mechanical engineering design, civil engineering design and software design and is increasingly found in more art-based design areas such as interior architecture, graphic design and product design.

The concept of professional design practice is helpful to managers of design teams and departments for several reasons, and especially if it is accompanied by third-party certification of competence. For example, many aspects of design managers’ responsibility and risk can be relocated to those who assess competence of design practitioners. If a design manager employs personnel who are certified as being professionally competent as designers in the appropriate field then this reduces the amount of responsibility that will fall on the manager in cases of failure and poor team performance. Instead, in cases of poor performance, a substantial amount of the responsibility and blame can be shared with staff members for not acting competently, and with the certifying authority for certifying designers who were not fully competent.

Standardisation in professional design practice is useful to design managers managing multi-disciplinary or complex teams. Standardisation enables managers to define and create design teams in terms of roles defined in terms of the competency, knowledge and skill in design practices accredited by professional design institutions. It remains then only for the manager to enlist staff certified to have these skills.

Taking an organisational overview from a constituent orientation perspective, professional design practices result in relatively homogenous sub-cultures in each sub-field of design (e.g. graphic designers). Sub-cultures of design sub-fields are typically heterogenous with each other – contrast say the subculture of mechatronics designers with that of advertising designers – that is, the whole design field is heterogenous. Of more importance in management terms, designer groups are often culturally heterogenous with other teams, units and departments in an organisation, which presents issues of management difficulty and poor performance (Tellefsen & Love, 2002). Problematising the concept of professional design practice is important in terms of understanding how and why designers and teams are problematic in many ways for improving design management, creating best practice results in business outcomes, and contributing to non-routine creative design solutions.

‘What have the limitations of professional design practice got to do with creativity, quality improvement and Mac computers?’ Everything. Non-routine creativity and quality improvement goes beyond the current states of professional design practice. In essence, professional design practice, like all kinds of professional practice, restricts designers to how things were done in the recent or long ago past. It is a structural encapsulation making professional skills and behaviours into ‘routine’. It changes what was ‘creative’, ‘novel’, and ‘innovative’ in the past into routine skills, competencies and processes that can be possessed or used by any competent professional design practitioner.

As discussed earlier, concepts of creativity and quality have to date been relatively naively addressed in the design and design technology literatures. Relatively uninspected ideas about professional design practice are used as the basis of development of computerised hardware and software support for designers. In art-based design sub-fields, the Mac computer and programs from, e.g., Adobe, Macromedia and Quark that facilitate designers in their professional practices have become viewed as ‘creative’. By extension, this has resulted in an assumption that processes and technologies used in design must inter alia support creativity and improvements in quality in design activity.

The Apple Macintosh and its software, and similar attempts to improve design outputs by , e.g. Xerox’s work with software such as Ventura and the resultant development of Corel Draw, have a primary focus on enabling designers with a particular skill set or level of competence, to produce work in a shorter time that appears more professional than expected. In the case of the Macintosh computer, much of the hardware design is closely linked to maximising performance in relation to graphic-based software used in the design sub-fields. In essence, these forms of software and hardware are closely tied to contemporary professional design practices both in terms of their outputs and in terms of their reasons for existence: to offer value in improving professional design outcomes.

Essentially, this is a focus on optimising the development of a restricted set of routine solutions: those produced within the bounds of professional design practices. This means that hardware and software such as that created by Apple and Adobe for the Macintosh platform acts to inhibit both the design of radically creative non-routine designs. It also acts to inhibit the types of quality management processes needed in design activities leading to non-routine design outcomes.

The differences in these two positions with regard to ‘creative’ hardware and software can be regarded in terms of radically different locations on an “integration-differentiation’ spectrum used as design heuristic. I developed this approach and model in unpublished undergraduate research at Lancaster University, UK, circa 1974. Design activity at the ‘integration’ end of the spectrum include racing cars whose elements are tightly integrated to reach highest performance in a use envelope that is narrow and well defined. In contrast, design activity at the differentiation end of the spectrum is suited to developing ultra flexible functioning outcomes in which their application is not tightly predetermined.

I am reminded of a tale about a customer waxing lyrical at a glazier's shop about the novelty of design of a particular rectangular piece of glass. ‘It’s just a piece of window glass!” protested the puzzled glazier. The customer immediately came back with, ‘Yes, but it is so novel! I’ve never seen a piece with exactly those dimensions.’ In essence, ‘creative’ hardware and software based on professional design practice supports the routine creation of many variants of the same thing.

This paper problematises the idea of professional design practice: differentiating between ‘routine’ designs and ‘non-routine’ novel, innovative design solutions. It combines a systems-based holistic perspective on professional design practice with critical review of assumptions in the design literature and public sphere about professional design practice and how it relates to design activity, design management and ‘creative’ software.

The paper outlines how professional design practice acts against and restricts creativity, and the creation of novel, non-routine and innovative designs, and inhibits the development of quality improvement processes supporting the creation of novel and innovative designs. Additionally, the paper draws attention to ways that computer hardware and software regarded as ‘creative’, e.g. hardware and software relating to the Apple/Mac platform preferentially propagates routine design outcomes and inhibits creativity and quality improvement in areas that are not routine.

Forrester, J. W. (1975). Counterintuitive Behavior of Social Systems, 1970. In J. W. Forrester (Ed.), Collected papers of Jay W. Forrester. Cambridge Massachusetts: Wright-Allen Press Inc.

VDI-Verlag. (1987). VDI GUIDELINE 2221: Systematic Approach to the design of Technical Systems and Products. Dusseldorf: VDI-Verlag.

Tellefsen, B., & Love, T. (2002). Understanding designing and design management through Constituent Market Orientation and Constituent Orientation. In D. Durling & J. Shackleton (Eds.), Common Ground. Proceedings of the Design Research Society International Conference at Brunel University, September 5-7, 2002. (pp. 1090-1106). Stoke-on-Trent: Staffordshire University Press.