This paper describes recent design research into prototypical ‘classes’ of designs for operational business systems for micro-businesses of 1-10 employees typical of traditional craft and contemporary information economies.

Business process design is an increasingly important and relatively new sub-field of design and design research. Its increasing importance is driven by three factors made more potent by information technology: increasing ability for very small business units to contribute to local and national economies; potential for increased efficiency of micro-businesses via reduction in Coasian transaction costs; increasingly competitive business environments leading to pressure on micro-businesses to deeply cut costs; and increased potential for improved design of micro-business processes to create significant benefits for the micro-businesses themselves and to local and national economies.

The analyses used in this paper combine Tellefsen's perspective on constituent orientation with Beerian Viable System analysis and Cashflow Quadrant analysis (Beer, 1972, 1988, 1989, 1995; Kiyosaki & Lechter, 2007; Tellefsen, 1995, 1999, 2001; Tellefsen & Love, 2003). These analyses are used to identify promising foci of design effort particularly with the intention of automating and systematizing business activities.

The paper first describes the importance of developing improved guidelines for design of organisational structures and business processes in the micro-business arena. It then outlines the structural, humanistic, financial, business management and computerized automation considerations that need to be addressed. Design issues are illustrated via mini case studies of three characteristic micro-businesses in the areas of publishing, plumbing, and rental investment. The paper shows how improvements to the design of business processes can be viewed through how four constituent orientations:

The paper concludes by integrating the outcomes of the above analyses into a preliminary checklist for the design of effective and efficient automated and systematized business processes for micro-businesses and small business enterprises.

Business process design, micro-business, viable systems, constituent orientation, cashflow quadrant analysis.

This paper describes research analyses exploring design strategies for improving the designing the organisation and business systems for micro-businesses. These were part of research undertaken by the author over the period 2004-2007 and focused on micro-business in the UK and Australia. For the research reported in this paper, micro-businesses are defined as having between 1 and 10 employees. Most micro-businesses are family-based firms, and many are ‘home-based’ businesses.

The approach used in the research assumed that micro-business business processes can be usefully regarded as complex socio-technical systems. This is justified on the grounds that the human aspects of micro-businesses are bound the potential of micro-businesses more significantly than in larger organisations, the overlap between social and technical activities is high (often the same person), and the compact nature of micro-businesses means that their systems are complex because they do not have the scale of larger businesses to simplify and optimize processes by teasing out individual systems functions into separate subsystems. That is, where larger businesses might have separate accounts departments, sales departments, design departments and manufacturing with separate groups doing each task, micro-businesses roll all of these together, and the tasks are often undertaken by a single individual. Viewing micro-businesses as complex socio-technical systems suggests that, like other socio-technical system design, it is helpful to understanding them to use multiple models drawn from the systems/business disciplinary boundary. This multi-modal approach is followed in this paper.

Improving the design of organisation structure and business processes for micro-businesses is important for three reasons. Worldwide, small and medium size enterprises (SMEs) dominate the business landscape and most SMEs are micro-businesses. Traditionally, micro-businesses are local in business effect and reach. Typically; micro-businesses include for example, local small retail shops and newsagents, construction subcontractors such as bricklayers and electricians, alternative therapists, business support services such as book-keeping and web design, and professional services such as lawyers and doctors.

Information and communication technology (ICT) increases the reach of many micro-businesses, their ability to better source expertise and business supplies, and increases their ability to contribute beyond their immediate context to national and local economies. Information and communication technologies also offer the potential for reduction in Coasian transaction costs of the business processes of micro-businesses. One example of this is in reducing the costs of professional micro-businesses in providing reports to clients. This was until recently a complex process involving typewriters, page setters, printers, freight and all the associated management activities. It can now be undertaken with a word processor and email. This use of ICT reduces both transaction costs and process time. Another example of the benefits of ICT is the reduction in transaction costs associated with dealing with banks and financial services. The increasing use of information and communication technologies in purchasing, sales and banking processes has massively reduced costs and time for micro-businesses that use them.

In parallel to the obvious benefits of ICT comes increased business competition. The increased reach and market extent made possible fro micro-businesses by information technology increases their exposure to competitors. It reduces the protection of spatial localization by which planners or natural competition reduces the number of micro-businesses in an area to those to which the area can support: usually resulting in a monopoly, oligopoly or informal cartel, all of which provide spatially-based competitive protection.

Gaining a competitive edge for micro-businesses in this information technology context is increasingly driven by the relative ability to make use of the advantages of ICT to provide competitive advantage by reducing costs, providing better service and being promoted and attractive to a larger range of potential and existing customers than others who are also using information technology. A significant issue is the potential to deeply cut costs through the use of access to information and computing technology (ICT) and the application of automation, both computerized and routines, to reducing the costs of supplying products and services and improving profits whilst reducing the costs for customers. Part of this is also developing increased ability to strategically use advertising, brand and image as competitive attractors for sales.

There is significant potential for design activity targeting improving the business processes of micro-businesses. Currently, business processes in micro-businesses are notoriously problematic and organisational structures can be less than supportive of growth. Many micro-businesses operate in an adhoc fashion without formal business processes and this contributes to the heavy failure rates typical of the sector. The design of business systems for micro-businesses is difficult because solutions must be simple and easy to use; whilst at the same time provide a comprehensive and integrated suite of processes that cover complexity intrinsic to many micro-businesses’s functioning.

This paper provides material to support the development of design guidelines for improving the design of business processes and organisational structures for the micro-business sector. It outlines the use of three perspectives in this task: Beerian Viable Systems Analysis, constituency orientation analysis and cashflow quadrant analysis. The purpose is to identify the best opportunities in terms of design effort – primarily with an interest in using ICT for automation and business process improvement.

The paper has four parts. The next section will outline the design factors that need to be considered in the design of business processes for micro-businesses. The third section explores the use of these factors in the context of three classic micro-business types. Section four reviews the implications for designing business process of different contextual understandings of business and business strategies from four constituencies of micro-business management. The concluding section provides a checklist for microbusiness process design derived from the earlier analyses.

Micro-businesses are complex socio-technical systems. Their complexity of business processes does not reflect their difference in size compared to larger businesses. Micro-businesses have to address the same basic business issues as found in any business. The ways that they do so, however, reflect their limited size and resources, particularly human resources, and deeply intermingle social and technical activities that would be separated out and optimized in larger organisations. An opportunity in improving the design of micro-business’s business processes is to use ICT to addresses these limitations.

A crucial difference between micro-businesses and larger organisations is the intensity of how business activities are tightly shaped by the limited and very specific resources of each individual micro-business in relation to structural, humanistic, financial, business management and computerized automation factors. Many of these in turn shaped by family circumstances (see, for example the research on Family business undertaken by Howorth, Hamilton and Rose at the Institute for Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development, Lancaster University, UK). The following lists some of the issues:

Designing business systems for micro-businesses require a different approach to design for larger businesses. Larger businesses can allocate resources to planning the use of business processes and systems and these activities are spread over several individuals who may have specialist training in each. In micro-businesses, all administrative and system development tasks, as well as the value production, customer management and business process and day to day operational tasks are simultaneously undertaken by a very small number of individuals – often one. This precludes gaining the benefits of specialization. Typically, the result is relative lack of skill in each task area, omission of some tasks, misunderstanding and errors in some business processes with delays in task completion, weak customer interaction and a general lack of efficiency and effectiveness in business functioning. The opportunity is to design business processes for micro-businesses to use ICT to reduce these problems.

The above issues offer the first dimension of a framework for designing business processes for micro-businesses.

Micro-businesses can be characterized by four typical constituencies of control, each with its own very different and very characteristic orientation:

Many micro-businesses are started by individuals who become self-employed and branch out on their own after previously working for another organisation. Typically, they become self employed to sell their technical skills. They commonly hire in business management expertise such as book-keeping, accounting, advertising etc. A second characteristic constituency is that of the business manager. In this case, typically the business manager is deeply involved in managing the day to day business activities of a small group of employees. Their focus is management of day to day operations. Rather than undertake technical tasks themselves, they employ others for creating outputs. A third constituency is that of the business owner. The focus of the business owner orientation is the strategic development of a business. That is, the business owner will typically employ a manager to manage the business and any employees. The final constituency is that of business investor. The investor constituency is involved in a micro-business to the extent that they invest capital in the business with the intention of gaining profit on that investment. Their involvement in the running of the business or its strategic development is typically minimal. For the business investor, the primary decisions are about which business operation to invest in. This contrasts particularly with the first constituency, whose focus is creating a ‘wage’ from the business.

For many micro-businesses, the roles of all four of the above constituencies are rolled together in someway. Regardless, the above constituencies are associated with specific and limited orientations involving decision making styles, foci of interest and modes of organisational learning (Tellefsen & Love, 2002). The upshot is that typically a micro-business is characterized by a single constituent orientation. In other words, micro-businesses themselves can be regarded as falling into four classes of organisation typified by the above four constituent orientations.

The above four classes of micro-businesses and management orientation map onto the four classes of business management used in the cash flow quadrant analysis approach of Kiyosaki and Lechter (2007). Kiyosaki and Lechter’s analyses suggest there are dramatically different business outcomes associated with each and that they lie in a spectrum in the order listed above with the advantage to the investor. In design terms, their analyses suggest and imply that there are benefits in designing organisational strategy to enable development from a ‘self-employed’ orientation of micro-business towards an investor orientation of micro-business.

The above analyses offer a second dimension of a framework for designing business processes for micro-businesses.

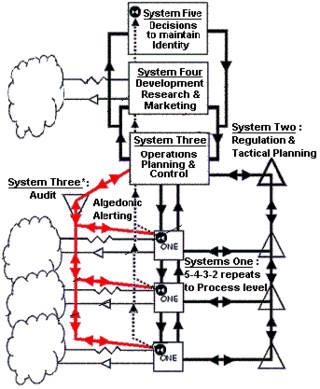

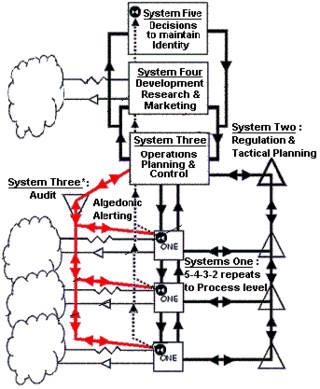

In system terms, micro-business behaviours, the factors of the second section and the above constituency approach can be located within Beer’s Viable System Model (Beer, 1972, 1988) as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Viable System Model (diagram by Green, 2007)

A viable system comprises five main subsystems. Systems 1 are sub-systems of a business that interact directly with the external environment (represented by the ‘clouds’) to undertake the main purposes of business. For example, in a small bakery these might include the shop, external deliveries to restaurants and backdoor sale of flour to home bread makers. Typically, there are several Systems 1. Each System 1 is also a complete system because the VSM is recursive. System 2 is the processes by which Systems 1 interact and are monitored and coordinated by the management activities of System 3. System 3 is the operational management sub-system between Systems 1 and Systems 4 and 5. It comprises all that is necessary to direct, monitor and manage Systems 1 (rules, rights and responsibilities). System 3 also includes an algedonic (fast pain/pleasure feedback) loop from Systems 1 to identify and manage unexpected events (for example, moldy loaves or sudden massive increase in sales of croissants). The focus of System 4 is gathering information from the external environment to inform long term strategy. System 4 provides evaluation and forecasting information to management systems 3 and 5. System 5 is the high-level management function and provides overall policy and long term strategic guidance for the whole organisation. For a more detailed description of the VSM approach see, for example, Beer (1989; 1995), Hutchinson (1997), Espejo (1989) and Waters (2006).

VSM applies to very small organisations because VSM subsystems can be shared and distributed across individuals’ roles and duties. The important thing is whether all the five essential subsystems and relationships exist in a suitably balanced manner.

The above VSM shows the minimum elements and relationships necessary for an organisation to be viable. Where an organisation is designed such that any of the VSM functions are missing or weak then typical organisational pathological development occurs. In micro-organisations these pathological organisational failures occur due to imbalance where some systems are emphasised more than others as occurs with the different constituent orientations above.

Morphologically, as organisational design forms, three of the four constituency orientations from the previous section map directly to the VSM. The fourth, the investor orientation, is functionally different.

For many self employed persons, their primary focus is Systems 1 – providing the services and products their business sells (Gerber, 1998). In effect, they are an operational employee of their own business. Systems 3, 4 and 5 along with System 2 are typically relatively weak or non-existent. Often, due to time and economic pressures, systems 3, 4, 5 and 2 are outsourced to professionals such as accountants and business advisers. Where these are implemented weakly, this organisational design of micro-business shows the classic pathology of stagnation, poor growth and undirected business activity with weak processes and accidental cashflow problems

Some micro-businesses grow and employ additional staff. The need to manage staff changes the focus of the self employed person’s role to that of business manager. This is a shift in emphasis towards System 3. In this characteristic design of micro-businesses, Systems 2, 4 and 5 become neglected as before. In many cases there is a tendency to use the System 3 algedonic fast action loop for all management activity. The outcome is the classic crisis-managed organisation. Similar examples of this occur in larger scale organisations such as universities and not-for-profits where System 1 employees are promoted to operational management roles without training.

There is a step change between the form of micro-business that emphasises the business owner orientation and the earlier two forms. The primary system focus of the business owner orientation is typically on the activities of systems 4, 5 and 2 assuming that systems 3 and 1 are managed by a business manager and employees. The business owner is interested in strategies for developing the micro-business and how it can best fit with the current and future environmental conditions (systems 4 and 5). In addition, to avoid the necessity of acting as an operational manager, the business owner will want to ensure that system 2 (auditing) is functioning well to provide system 3 (and hence systems 4 and 5) with sound ongoing information about how the micro-business is functioning. Design failures of the business owner orientation are of weaknesses in communication between systems 4 and 5 and systems 1, 2 and 3 leading to either lack of understanding of the business or lack of influence on and guidance of the operational manager. In either case, the business can travel in a different direction from the intended strategy until crisis of one form or other occurs. This is found in for example in small franchising chains where franchisees do not accurately implement the franchising model.

The investor orientation is functionally different from the above three orientations. For the investor in a micro-business, their concern is of successful ‘whole of business’ functioning. They wish the micro-business to make money for them. They are not directly interested in the activities undertaken at Systems 1, i.e. what the business does. Their primary focus is in the profit predictions of systems 5 and 4 management and how well their strategies are likely to be implemented to produce these profit outcomes. In system design terms, the focus of the investor orientation is ‘whole of system’, i.e. how well systems 1 to 5 are implemented in the organisation design. Design failures from an investor orientation occur where systems are missing, illusory or deviant and displaced by alternative systems. The latter occurs in situations of organisation failure where for example, management and staff are involved in theft from the organisation or the organisational function is subverted to divert resources or profits elsewhere, i.e. where managers, staff and sub-contractors line their pockets at the expense of the micro-business as a whole. Classically, the pathological organisation failures of ‘whole of organisation’ investor orientation occur as ‘whole of organisation’ malfunctioning or corruption.

Three brief case studies of micro-businesses illustrate some of the above issues:

This micro-publishing business focuses around a single individual undertaking all aspects of the business. Profitability depends on producing books and selling them.

In organisational design terms, this business is complex with multiple Systems 1:

All Systems 1 are undertaken by the owner/manager except for advertising and promotion which is subcontracted. Substantial parts of Systems 2 and 3 are automated mainly via a designed combination of accounting software, custom computer systems and internet-based ecommerce software. The remainder of the functionality of systems 2 and 3 are undertaken in parallel to Systems 1 and 2 by the same individual. Systems 4 and 5 activities happen in an ad-hoc occasional manner.

In system design terms as described above, this micro-business focuses primarily on constituent orientations of business manager and self employed. A key differentiator of the business manager and business owner orientations is a focus on building the business so it can be sold and this did not form part of the business strategy. There was no evidence of the investor orientation. This is not surprising because the business is primarily a knowledge-based business and does not require substantial capital investment at its current level of functioning.

Classic design failure modes for this type of organisation are three fold. The complexity at Systems 1 requires good System 3 management and failures at this level lead to failures of disorganization. The second failure dynamic is that of overload with too many tasks being undertaken by the same individual. The third and perhaps most important is that the overload in complexity and workload at levels 1 to 3 leads to weakness in systems 4 and 5. This means that strategy is relatively unresponsive to environmental changes and the necessary attention of systems 4 and 5 is not available for guiding business growth and hence this arrangement tends to stagnation.

In design terms, there are opportunities for redesigning the micro-business to either delegate more tasks at System 1 or increase automation thus freeing more attention to higher level management tasks and systems.

This organisation design of micro-business is typical of the home-based businesses in the construction sector. The business primarily provides licensed plumbing services to domestic premises with occasional light industrial work and plumbing in new constructions. The business is a husband –wife partnership with the children (now young adults) employed by the business. In organisational design terms, this business is relatively simple as its Systems 1 comprise:

Plumbing is a licensed trade and subject to training and standardization on the practical services. This significantly reduces the management load at Systems 1 and 3 and the activities of System 2. In effect much of the work of Systems 1are distributed between all participants. In addition, the advertising is outsourced. Systems 2 and 3 are jointly undertaken by husband and wife. All administrative activities are undertaken by the wife. Systems 4 and 5 activities are undertaken sporadically by husband and wife, typically at time when it is necessary to renew or modify advertising arrangements

In system design terms, this business has primarily a self-employed constituent orientation. The focus of the business is primarily to provide wage income for all its participants. In parallel, but separately, exists an investor orientation in which the profits from the business are invested elsewhere. This is a classically successful strategy (see Cashflow quadrant).

Classic design weaknesses of this organisational form are that much of the business process, strategy, mission and operational management are strongly shaped by the licensing of plumbing. This is the down side of the efficiencies and oligopolic benefits that licensing brings. It removes key advantages of micro-businesses – flexibility and ability to quickly change direction. It makes it hard for the micro-business to adapt to new business opportunities if other markets present themselves.

In organisational design terms, the opportunities are to develop a multi-pronged business in which the strengths and financial stability of the licensed business processes are complemented by a parallel high risk- high gain business in another realm.

This case study is of the design of organisation and business processes for a micro-business that specialises in buying residential property to let, with the income from the letting contributing to payment of the financial costs of purchasing the building and improving its appearance and value. The primary profit is the positive change in value of the properties over time.

This business is investment driven and has an investor orientation. The aim is to make profit on selling whilst undertaking business processes that will improve the potential outcome whilst minimising costs. This can be seen as primarily two Systems 1 processes:

System 3 provides the coordinated management of this process, in particular, the management of the letting and upgrading. In the case study, much of Systems 1, 2 and 3 are outsourced and in effect automated. The focus of the couple owning the business are characterised by an investor orientation. That is their attentions and commitments are primarily on Systems 4 and 5.

Classic design weaknesses of this organisational structure are the weaknesses of poor information and the timing of feedback. All designed systems involve transfer of information, actions and feedback of information on those e actions. All of these take time. From the perspective of those primarily involved in Systems 4 and 5 undertaking strategic planning, they see only a simplified snapshot of system behaviours. This is essential otherwise they would be overrun with data. In rapidly changing situations, errors of information or poor timing can result in sub-optimal strategies being imposed on Systems 1, 2 and 3.

The design opportunities of this context are to improve the quality and timing of information for Systems 4 and 5 whilst maintaining the attenuation of information appropriate to these executive management levels.

From experience of undertaking this research, the data needed for undertaking the above analyses and guiding the design of organisation and business process for micro-businesses can be relatively quickly gathered via a semi-structured interview using questions checklist such as:

Is the drive for the owner manager to be:

Does the business employ family?

Opportunities for automation of

Opportunities for delegation:

Limits and bounds

New market opportunities:

SWAT analysis

Porter 5 Factor analysis

Sub-systems

Business structures

This paper has reviewed ongoing research in organisation and business process design in the realm of micro-businesses. In particular, it has focused on the application of three complementary and triangulating conceptual frameworks as a basis for developing design guidelines: viable system model, constituent orientation analysis and cashflow quadrant analysis. The generic approaches used in the research, including the use of a data gathering question checklist, were described.

Further research will explore the organisational design differences between micro-businesses that stabilise at a fixed size (or stagnate and fail) and those that grow.

Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm. London: The Penguin Press.

Beer, S. (1988). Heart of Enterprise. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd.

Beer, S. (1989). The Viable System Model: its provenance, development, methodology and pathology. In R. Espejo & R. Harnden (Eds.), The Viable System Model: Interpretations and Applications of Stafford Beer's VSM. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Beer, S. (1995). Diagnosing the system for organizations. Chichester: Wiley.

Espejo, R., & Harnden, R. (Eds.). (1989). The Viable System Model: Interpretations and Applications of Stafford Beer's VSM. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Gerber, M. E. (1998). The E-Myth Manager: Why Most Managers Don't Work and What to Do About It. New York: Harper Collins.

Green, N. (2007). VSM figure. In Vsm.gif (Ed.) (Vol. 343 x417 pixels, pp. Diagram of Viable System Model (VSM) of Beer): GFDL and wikipedia.

Hutchinson , W. (1997). Systems Thinking and Associated Methodologies. Perth, WA: Praxis Education.

Kiyosaki, R. T., & Lechter, S. L. (2007). The Cashflow Quadrant. London: Sphere.

Tellefsen, B. (1995). Constituent Orientation: Theory, Measurements and Empirical Evidence. In B. Tellefesen (Ed.), Market Orientation (pp. 111-156). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Tellefsen, B. (1999). Constituent Market Orientation. Journal of Market Focused Management, 4(2), 103-124.

Tellefsen, B. (2001). Market orientation and partnership learning in product development and design. In S. Ilstad (Ed.), Industrial Organization and Business Management (pp. 396-405). Trondheim: Tapir Akademiske Forlag.

Tellefsen, B., & Love, T. (2002). Understanding designing and design management through Constituent Market Orientation and Constituent Orientation. In D. Durling & J. Shackleton (Eds.), Common Ground. Proceedings of the Design Research Society International Conference at Brunel University, September 5-7, 2002. (pp. 1090-1106). Stoke-on-Trent: Staffordshire University Press.

Tellefsen, B., & Love, T. (2003). Constituent Market Orientation as a Basis for Integrated Design Processes and Design Management. In Proceedings of the 6th Asian Design Conference. Tsukuba.

Waters, J. (2006). The VSM Guide. from http://www.esrad.org.uk/resources/vsmg_3/screen.php?page=home